|

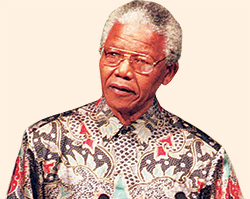

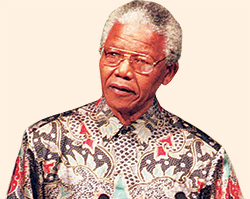

HOW NELSON

MANDELA'S EXAMPLE OFFERS STYLE LESSONS

By Vanessa

Friedman

"Nelson Mandela clearly took clothes - and their

power - seriously, and perhaps we should,

too".

Example,

Jerry Bird, Publisher and Editor of Africa

Travel Magazine will wear often a "Madiba

shirt" and African hats with pride in Africa,

USA and Canada.

Almost a

month after the death of Nelson Mandela, every

talking head has sighed in with their own memoir

or eulogy so what is there to add? Fair question

Let me simply say that this is a new year’s

column – a look forward, not a look back – and

it is about a lesson I think worth taking from

Mandela and applying in 2014, a lesson not

included in the many “Lessons from Mandela”

written in recent weeks. Most of these were

concerned with choosing reconciliation over

revolution, while this is to do with clothes. It

may seem like a frivolous topic where someone

such as Mandela is concerned, except he clearly

took clothes – and their power – seriously, and

perhaps we should, too.

Picture any G8 or even G20 meeting and, women

aside, there is a startling homogeneity to the

dress, the theory being that those who dress

alike, negotiate alike. As the former Indonesian

vice-president Jusuf Kalla was quoted as saying:

“Nelson Mandela dared to wear batik in the UN

General Assembly. If it was me, then I might

still hesitate to wear batik and speak in the UN

General Assembly, but he did not.”In a

world where leaders rarely stray from an

accepted uniform, no matter where they live –

dark suit, white or blue shirt, red or blue tie

– Mandela stood out in his colourful batik

shirts. They not only made him visible wherever

he went but served a variety of more covert

purposes: advertising his independence from what

went before, underscoring his allegiance with

the traditions of his country and providing a

form of outreach to minority groups that each

interpreted in their own way.

More than any leader I can think of, Mandela

demonstrated how clothes can be a strategic

expression of individuality, even for a

politician. And he did it without adopting

another widely used uniform, the military jacket

– the general default option ever since

Napoleon.

Consider the fact, however, that, when he was

elected, Mandela wore a suit and tie just like

every other man in his position. It was only

after a few months that he began to wear batik –

and wear it, and wear it, to the extent that it

became so synonymous with his image that it took

his name (the “Madiba” shirt), and when Giorgio

Armani offered to dress him, he respectfully

declined.

Mandela had found his signature. It meant: (a)

anyone else who wore batik automatically became

associated with him; and (b) when he chose to

change from it, it was an act loaded with

meaning. See, for example, when he wore a

Springbok jersey in the 1995 Rugby World Cup,

and the following year when he wore a “Bafana

Bafana” football shirt for the African Cup of

Nations. Not to mention his willingness to bend

his own rules when necessary. According to the

designer Oscar de la Renta, Mandela was once

invited for dinner at the home of Harry

Oppenheimer, then-chairman of De Beers – “as

long as he wore a tie”. He wore the tie.

. . .

Like most symbols, the Madiba shirt became the

subject of several origination myths. On the

Judaism website chabad.org,

a writer called Avraham Berkowitz recalls a

conversation with Mandela about a visit to a

Jewish synagogue in Cape Town in 1994 when a

woman in the congregation gave him a

black-and-gold fish-print shirt. According to

Berkowitz, Mandela said: “After I’d worn that

shirt, this same woman [white South African

designer Desré Buirski] would continue to send

me shirts. We become good friends, and she

designed hundreds of shirts for me. These shirts

help me carry my message all over the world.”

South African GQ, however, also attributes

the shirts to fashion designer Sonwabile Ndamase,

and points out that “by wearing fabrics rooted

in southeast Asian cultures, Mandela reached out

to the Cape Malay community of South Africans”.

Burkina Faso-born tailor Pathé Ouédraogo is

another reported provider of Mandela’s shirts.

Meanwhile, Indonesia has hailed Mandela for

helping to make its batik globally known. It is

said that President Suharto gave him his first

batik shirt when Mandela visited the country

shortly after his release from prison, and he

also went on to wear many shirts by Indonesian

designer Iwan Tirta. Mandela’s batik shirts were

seen in Indonesia as a symbol of the parallels

between South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement

and its own anti-colonial movement.

Whatever the reality (and Mandela probably wore

shirts by all of the above during his long

batik-wearing career), it is clear this garment

was not a bad communication tool. With clothing,

as with politics, Mandela made different

individuals feel connected to his cause and used

his clothing to further his politics.

It is a model that other politicians might do

well to consider. Suits are, no question, the

safe option. Perhaps it’s time to think more

broadly, not just about constituencies but about

what constitutes imagineering. That is a

resolution worth making in 2014.

MANDELA SPURS TOURISM SURGE

South Africa is expecting a tourism boom

following Mandela’s passing, coinciding with

the release of the new film biopic ‘Mandela:

Long Walk to Freedom’ in January 2014, the

Herald Sun reported.

“Not only is there a significant influx of

foreign visitors to our destination, but

domestic travel will rise too as people

travel to attend memorial events, to be

present at the funeral in Qunu and embark on

the annual festive season holiday period,”

South African president Jacob Zuma said.

More than 100 current and former heads of

state travelled to South Africa in order to

attend the national memorial service for

Nelson Mandela at FNB Stadium in Nasrec

yesterday.

Visitors to South Africa can visit Mandela’s

home town, the prison where he was jailed

for 27 years and eat at the Mandela family

restaurant, all in attempt to understand a

nation’s battle for liberty.

Tourists can visit Robben Island, now a

World Heritage listed site, where Mandela

was locked away from 1963 to 1990, plotting

the abolition of the racist apartheid

regime.

“Mandela opened up our beautiful country to

the rest of the world and his name alone has

attracted millions of tourists wanting to

walk in his footsteps to South Africa every

year,” South African Tourism chief executive

Thulani Nzima said.

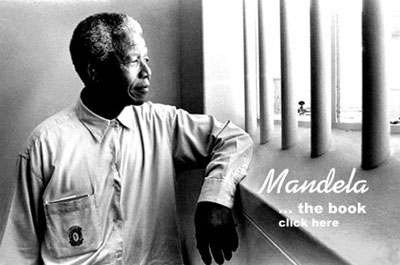

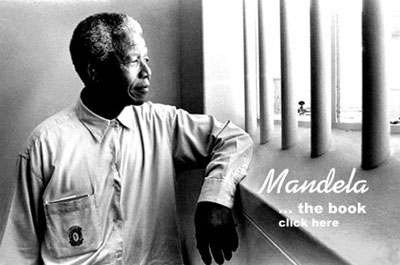

Mandela ... The

Book

Mandela-

the Book:

Just recently our editorial staff received

a beautifully bound book on the life and

times of Nelson Mandela, South Africa's

gift to the world. We will present our

review of this timely treasury on this

website and in coming editions of Africa

Travel Magazine. We will also give you the

details and how you can obtain your

personal copy, which we are sure yoiu will

value for a lifetime. Jerry W. Bird,

Editor

Profile

of Nelson R.

Mandela

From

ANC Web Site

Nelson

Mandela's greatest pleasure, his most

private moment, is watching the sun set

with the music of Handel or Tchaikovsky

playing. Locked up in his cell during

daylight hours, deprived of music, both

these simple pleasures were denied him for

decades. With his fellow prisoners,

concerts were organized when possible,

particularly at Christmas time, where they

would sing. Nelson Mandela finds music

very uplifting, and takes a keen interest

not only in European classical music but

also in African choral music and the many

talents in South African music. But one

voice stands out above all - that of Paul

Robeson, whom he describes as our hero.

The

years in jail reinforced habits that were

already entrenched: the disciplined eating

regime of an athlete began in the 1940s,

as did the early morning exercise. Still

today Nelson Mandela is up by 4.30 am,

irrespective of how late he has worked the

previous evening. By 5 am he has begun his

exercise routine that lasts at least an

hour. Breakfast is by 6.30, when the days

newspapers are read. The day s work has

begun.

With a

standard working day of at least 12 hours,

time management is critical and Nelson

Mandela is extremely impatient with

unpunctuality, regarding it as insulting

to those you are dealing

with.

When

speaking of the extensive traveling he has

undertaken since his release from prison,

Nelson Mandela says: I was helped when

preparing for my release by the biography

of Pandit Nehru, who wrote of what happens

when you leave jail. My daughter Zinzi

says that she grew up without a father,

who, when he returned, became a father of

the nation. This has placed a great

responsibility of my shoulders. And

wherever I travel, I immediately begin to

miss the familiar - the mine dumps, the

color and smell that is uniquely South

African, and, above all, the people. I do

not like to be away for any length of

time. For me, there is no place like

home.

Mandela

accepted the Nobel Peace Prize as an

accolade to all people who have worked for

peace and stood against racism. It was as

much an award to his person as it was to

the ANC and all South Africa s people. In

particular, he regards it as a tribute to

the people of Norway who stood against

apartheid while many in the world were

silent.

We know

it was Norway that provided resources for

farming; thereby enabling us to grow food;

resources for education and vocational

training and the provision of

accommodation over the years in exile. The

reward for all this sacrifice will be the

attainment of freedom and democracy in

South Africa, in an open society which

respects the rights of all individuals.

That goal is now in sight, and we have to

thank the people and governments of Norway

and Sweden for the tremendous role they

played.

More of

Nelson Mandela Profile to

come

REMEMBERING

MANDELA COURAGE AND TRIUMPH

I

remember where I was when Nelson Mandela

died on December 5, 2013: at work, preparing

for an important meeting. When I heard the

news, I did not want to be at the office. In

Vancouver, it was business as usual;

halfway around the world, though, the

Rainbow Nation started to grieve. When I

left my downtown office and walked onto a

dark Vancouver street, I suddenly felt a

deep sense of loneliness and loss. Although

Mandela was basically a stranger to me when

I was assigned to guard him as a member of

his security detail, a close bond based on

trust and protection quickly developed

between us. I worked with Mandela from May

1994 until February 1996, and on my last day

with him, I told him he was like a

grandfather to me; he leaned over, put his

hand on my shoulder, and said, “You are my

son.”.

Heading

home on a packed SeaBus, I wondered how many

people sitting there with me had heard the

news. How many of them knew what Mandela

meant to

South Africa? Later that evening I sat

in silence, watching the images of an

ever-growing crowd outside Mandela’s home.

Many mourners were quietly paying their

respects, appearing to inwardly reflect with

their own personal thoughts. But I also saw

the uplifting images of small groups of

people clapping, singing, and smiling. In

that moment, I more fully understood the

meaning of celebrating someone’s life when

they die. I felt I needed to go back to

South Africa—where I was born and lived for

33 years before moving to Vancouver—to be

there during that time of national grief. My

decision was partly because of my respect

for him, but mostly because of a gesture

from him to me more than 13 years earlier.

In May 2000, less than a year after

immigrating to

Canada, my wife passed away following a

scuba-diving accident. I went back to South

Africa for her memorial service, and while I

was there, Mandela called me to express his

condolences. He was no longer the president,

yet he still took the time to call me. I

wanted to go back as a show of appreciation

for his kind, heartfelt words all those

years earlier. I knew that, because of tight

security, I would not make it to the actual

funeral. However, I just wanted to be on

South African soil, closer to Mandela.

So on

December 11, I boarded a plane to South

Africa. That day I started reading Mandela’s

autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom.

I have a treasured copy of the book with a

personal message from Mandela inscribed in

it, which says, “Compliments and best

wishes”. What makes the message special is

that he acknowledged my rank—major at the

time, even though I had come through the

lower ranks while I was in the pre-democracy

police force—that he wrote it in Afrikaans,

and that it was signed on Christmas Day

(1995). Mandela signed it while we were with

him in Qunu, his childhood village. He

always took the time to tell us that he

appreciated the sacrifice we made in giving

up our time with our loved ones to accompany

him on trips around the world and to his

village, sometimes for as long as three

weeks, and sometimes over the festive

season.

On one

such trip, around Christmas Day, hundreds of

local villagers were invited by Mandela to

his home for a meal. Mandela had bought

several sheep for the occasion, and some of

the men proceeded to slaughter them and cook

the meat on open fires. We bodyguards

watched this all from a distance, some of us

seeing something like this for the first

time in our lives. Later we helped carry the

meat to Mandela’s kitchen, and I noticed

that it still looked a bit raw. When I

walked into the kitchen, carrying a large

plate stacked high with chunks of partly

cooked meat, Mandela exclaimed, somewhat

mischievously, “Ah, Etienne, you must have

some meat!” He probably realized I was used

to buying meat from a butcher and cooking it

on a grill or in an oven. I felt obliged to

accept his offer, and managed one or two

mouthfuls before finding an excuse to go and

check something outside.

I told him he was like

a grandfather to me; he leaned over, put his

hand on my shoulder, and said, “You are my

son.”

Though I

cherish my copy of Mandela’s book, I had

never actually read it until that plane ride

back home. I always used to joke, “I know

the story, I don’t need to read it”; but in

reality, I did not know the story. Over the

coming days, I would get to know Mandela

better, after his death. I landed in South

Africa on December 13, the last day Mandela

lay in state at the Union Buildings. I

arrived at the buildings a few hours after

landing, only to discover that I might not

make it into the area where thousands of

people were lining up to file by him. This

was because only those arriving on buses

from designated gathering zones were allowed

into the area where I needed to be. Not

knowing this arrangement, I had gone

directly to the buildings. So I took

advantage of the somewhat disorganized crowd

control and tricked my way into the area,

joining one of the lines of people. I

remember thinking, “I’ve come this

far—there’s no way I’m not going to say

goodbye to my president.” Several hours

later, I filed past Mandela. I promised him

I would try to be more like him, and that I

would tell as many people as possible about

him. As I left the Union Buildings, I

recalled his words: “Death is inevitable.

When a man has done what he conceives to be

his duty to his people and his country, he

can rest in peace. I believe I have made

that effort, and that is why I will sleep

for eternity.” Mandela was buried on

December 15. The following day was South

Africa’s first day “without” him. It was

also the Day of Reconciliation, and has been

known as such since 1994, when Mandela

became president.

I awoke

at 4:50 a.m., still jet-lagged. It was

raining lightly and my thoughts drifted to

Qunu, where he now rests. Mandela was a

private person. Though I spent a lot of time

with him, he never shared any stories about

his childhood with me. Sometimes when we

walked through the rural areas around his

village, he would point to hills where he

used to play, but he never shared any

intimate recollections of his upbringing. He

did, however, frequently ask me about mine.

One of my most special trips with Mandela

was when we visited my hometown together on

an official visit, where he spent most of

the day meeting local farmers and community

leaders and addressing a stadium full of

people at a public gathering.

Someone

once said to me, “You walked beside a god.”

I know what that person was trying to say,

but it also made me realize, once more, what

an exceptional person Mandela was. He was

not a god; he was human. For me, he will

never die. He chose not to concentrate on

past grievances, but rather on

reconciliation. He showed that through

tolerance, patience, and understanding, you

can change how people think and act. When

Mandela called me all those years ago, he

said, “You have the courage to turn tragedy

into triumph.” And that is what this story

is about: courage and triumph. That is how I

remember Mandela.

|